Northern Ireland's Heritage at Risk: The Giant Cause

Northern Ireland has a fantastic built heritage but it has been severely neglected. It’s time that changed, writes Lydia Franklin.

Shockingly underfunded and undervalued, Northern Ireland’s historic buildings fight the odds for their survival. At the forefront of the battle is the Ulster Architectural Heritage (UAH), an independent organisation which has campaigned for over 50 years for historic buildings in Northern Ireland and the nine counties of Ulster.

In conversation with the UAH’s heritage projects officer, Sebastian Graham, it became blazingly apparent just how disadvantaged historic buildings are in Northern Ireland. While funding for the historic environment hits ‘an all-time low’, as Graham observed, the value placed in historic buildings plummets with it.

If funding is the key to saving Northern Ireland’s heritage, it is time to unlock the wealth of challenges that afflict the country’s historic buildings.

‘Land banking in Belfast city centre is a major issue especially in North Street and Royal Avenue. Many of these key historic buildings are lying empty and their condition is deteriorating.’ – Sebastian Graham, UAH Heritage Projects Officer.

Northern Ireland’s capital boomed during the 19th century with fast-growing linen and shipbuilding industries, and the architectural survivals from this period are magnificent. These are handsome, sandstone buildings often with opulent carvings and arched windows.

Where these buildings are allowed to shine, they do so brilliantly in Belfast. Like a richly ornamented chocolate box, the late 19th-century Italianate bank building, now known as the Merchant Hotel, has become a coveted spot for a luxurious night’s stay in the city.

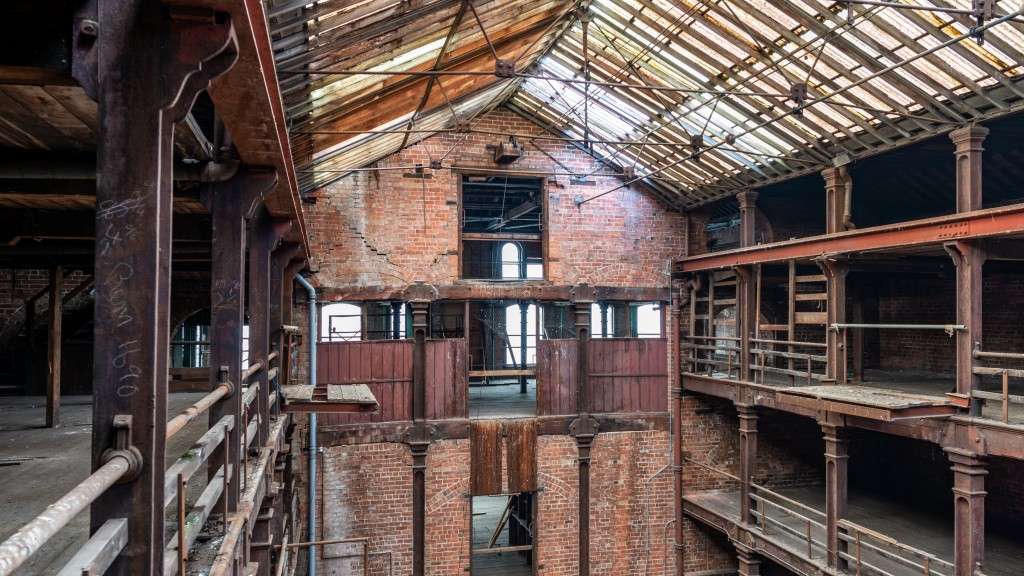

Just around the corner is Riddel’s Warehouse, built in 1867 for the ironmongers John Riddel & Co, with a nearly untouched lofty and atmospheric interior that steps you right back in time. This rare survival is currently being carefully and thoughtfully restored by the Hearth Historic Buildings Trust who are working to secure a viable future for the building.

And yet these are anomalies for Belfast. The Old Town Hall occupies a prominent spot within the city and is a fine architectural specimen, and yet it has recently been highlighted on SAVE’s Buildings at Risk register.

Ulster Architectural Heritage reveal that the number of historic buildings on Northern Ireland’s Heritage at Risk register have almost doubled over the last three years, from 600 in 2020 to 1,098 in 2023.

A walk around Belfast’s city centre reveals many more vacant and visibly uncared for historic buildings. Take, for example, the neglected North Street just west of Belfast’s Cathedral Quarter which was once Belfast’s historic trading centre and has recently emerged as a thriving culture and arts hub. In 2016, three Victorian buildings from Nos 95 to 107 North Street were reduced to rubble, leaving the city’s impressive, art deco Bank of Ireland marooned and deprived of any immediate urban context. The now demolished buildings were once pleasing additions to the street; mismatched but rhythmically in tune with one another. They were calling out for some care and attention but instead were served with demolition just days before their listing application was to be reviewed. Now, no amount of bright and eye-catching street art can distract from the gaping plot of land which has been left abandoned along with the plans to redevelop this part of Belfast after funding was withdrawn.

The future is not looking bright for those building that have managed to survive on North Street either. The once striking grade B1 listed art deco arcade, built in the 1930s, is now little more than a shell after an arson attack in 2004. It currently faces potential demolition and facadism as part of the contentious development plan for Belfast’s Cathedral Quarter, named “Tribeca Belfast”.

Why has so much of Northern Ireland’s architectural heritage been left shuttered and abandoned, poised for decay or demolition? Rita Harkin, an authority on conservation in Northern Ireland, said it best when she wrote, “In...the post-conflict environment, a culture has emerged that prioritises short-term profit over long-term sustainable regeneration”. This, she stated, has been more damaging to Northern Ireland’s built environment than the Troubles themselves. In Belfast, as the city hurried to recover itself from the conflict, the door was flung wide open to any and all development.

Today, planners have struggled to shed this attitude that all development is good development, to the direct detriment of the area’s historic fabric. This attitude proliferated to Northern Ireland’s rural dwellings too, fostered by a government scheme run widely in the late 1990s and early 2000s known as the Replacement Dwelling Scheme. This granted owners a sum £30,000 (VAT-free) to knock down an old rural dwelling, often a vernacular cottage, and build a brand new one on its grave.

In 2015, all funding from Northern Ireland’s central government through the listed building grant aid was suspended. When funding resumed in 2016-17 following departmental restructuring, it was cut from £4.6m to £500,000 for all listed buildings in Northern Ireland. Presently, funding streams have been closed for 2023-24 until May, when it reopens for the following year. Even then, the funding which is available is vastly inadequate. The £6,000 available for restoring a historic roof is spent, as Graham highlighted, on scaffolding and “that’s before you even touch the building”.

This puts the financial burden of maintaining listed buildings heavily on the shoulders of owners. Those with a desire to restore a historic building are often priced out of doing so. Graham observes that this especially shuts the door in the face of a younger generation who might be interested in beginning a heritage project.

The overriding problem across Northern Ireland is the lack of value that is placed in the country’s historic buildings. This goes hand in hand with a lack of funding, but it seems at times those lines get conveniently blurred.

The UAH, for example, have found that local councils are “reluctant” to serve Urgent Works Notices even when directly called on to do so. This follows the devolution of planning powers from central government to the local councils in 2015. As a “discretionary power” now held by the councils, too much emphasis has been placed on “discretionary” as a get-out-of-jail-free card. However, as councils have rebutted, when they were granted these powers in 2015, they did not receive any funding to support them.

And so, we circle back again to the dearth of funding for the historic environment. An unwillingness to serve Urgent Works Notices leaves vacant and deteriorating buildings in purgatory. Graham highlighted that these powers should be seen as positive forces to save vulnerable historic buildings and stimulate change. It is time this is seen more widely as a good and worthy cause.

As the number of listed buildings on Northern Ireland’s Heritage at Risk register climbs upwards, this is a critical stage for Northern Ireland’s built heritage. It is vital that the heritage sector receives greater funding to alleviate the financial strain placed on owners, to help free historic buildings from the perception of being a burden and to promote the now crucial message of sustainable reuse.

It is time to make some noise about the value of Northern Ireland’s historic buildings and to champion what we have left – while there is still time.

ENDS

Notes to editors:

1. For more information and images contact Elizabeth Hopkirk: elizabeth.hopkirk@savebritainsheritage.org / 020 7253 3500.

2. SAVE Britain’s Heritage is an independent voice in conservation that fights for threatened historic buildings and sustainable reuses. We stand apart from other organisations by bringing together architects, engineers, planners and investors to offer viable alternative proposals. Where necessary, and with expert advice, we take legal action to prevent major and needless losses. Our success stories range from Smithfield Market in London and Wentworth Woodhouse stately home in Yorkshire, to a Lancashire bowls club and the Liverpool terraces where Ringo Starr grew up.