Just the tonic

5th July 2023

Pubs are vital pillars of their communities, yet more than 150 closed in the first three months of this year. Cristina Monteiro and Dr David Knight consider what is at stake when last orders are called.

What do we mean when we talk about saving the pub? Are we trying to protect a particular condition, building fabric, feeling or function? Are we trying to revive something on its way to the history books, or to find new uses and purpose in a changing, increasingly isolated society? We have been considering these questions for some years now, most recently in our book Public House: A cultural and social history of the London pub (Open City, 2021).

We believe that valuing – and protecting – the heritage of the pub is a complex issue that touches on not only architectural heritage but also social history, and raises broader issues of how the fabric of our built environment is maintained, protected and allowed to evolve.

The way we “do” heritage in the UK feels like a very blunt instrument when presented with the humble pub. It is currently extraordinarily easy to transform a pub into a small supermarket or private dwellings, or to reduce it to a ground-level retail unit surrounded by other development. To oppose this sort of shift we typically rely on the pub’s architectural significance to get it locally or statutorily listed, and this reliance usually ends in two ways: either the pub is lost entirely (because it’s not deemed significant) or the building is retained but as a shell with a parasitical “express”-style supermarket inside. We may have retained the fabric of the pub, to some extent, but we have lost the pub as a social space. The stones remain but the pub has gone – taking its social and cultural significance with it.

STORYTELLER - Ye Olde Mitre, Hatton Garden, London

IMAGE: Ye Olde Mitre, Holborn (Credit: Andrea di Filippo)

Some pubs tell wider social and spatial histories of the places in which they sit. Ye Olde Mitre, in an alleyway off Hatton Garden, is a literal storyteller: its built fabric, spaces and walls speak of the area’s curious history as part of Cambridgeshire – a relic of its location in the shadow of the Bishop of Ely’s palace. A cherry tree embedded in the Mitre’s facade still marks the boundary of the Bishop of Ely’s land, and drinking in this context feels like inhabiting the cloisters and courts of the mediaeval city.

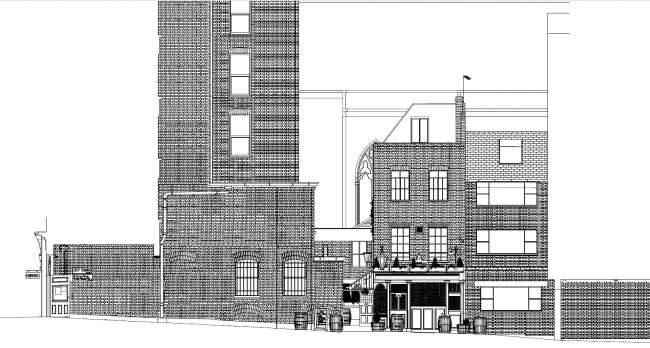

CROSS SECTION: showing Ye Olde Mitre in context, hemmed in by buildings on all sides, creating a secret courtyard only accessible by the passageway between Hatton Garden and Ely Place (Credit: Yemi Aladerun, Stuart Darling, Alex Jenkins and Rob McCarthy, courtesy of Open City)

The kinds of significance raised by this example – intangible, social, cultural – are far harder to protect. Even legislation which acknowledges value beyond the physical, such as “Asset of Community Value” protection, merely gives a community a temporary opportunity to purchase a pub in the face of development, and while this has proven a useful tool in some circumstances, a community’s capacity to invest in a substantial building shouldn’t be the only way that protection is conferred.

But when we talk about social and cultural significance, what do we mean? There is no single answer because the pub, as a social construct, a business and an architectural typology, has experienced extraordinary transformation and reimagination over the centuries. Pub types have merged, disappeared, hybridised, evolved, rebooted and generally got incredibly and delightfully confused over the centuries. Some places that we identify as pubs today are fiercely independent small businesses, while others are part of substantial, sometimes global, commercial operations. Some are on quiet country lanes, others are in the departure lounge or embedded within our cities, towns and suburbs. Some were purpose-built, others evolved out of a diverse range of existing buildings. Some are extraordinarily rich, purposeful or crafted structures – inside and out – while others are architecturally insignificant.

ARCHIVE - The Square and Compass, Worth Matravers, Dorset

IMAGE: The Square & Compass in Dorset (Credit: Alamy)

Sometimes the collection on the walls of a pub is one of its most precious assets, and pubs often function as informal museums of local history. The Masons Arms in Teddington, Richmond, has a finer collection of beer memorabilia and breweriana than any museum of industrial heritage I can think of. A whole room of the Square and Compass in coastal Dorset is dedicated to the fossil and natural history collection of two generations of pub landlord, Raymond and Charlie Newman.

SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE - The Wenlock Arms, Shoreditch, London

IMAGE: A typical scene outside The Wenlock Arms in spring 2023 (Credit: The Wenlock Arms)

Society needs places that draw people together and which promote difference. Pubs that really achieve this state often have a visionary landlord or other key figure to thank, and often the most socially important pubs are those without much potential for statutory listing. The Wenlock Arms has for some decades been just such a social condenser, over the years becoming a hub for old-school jazz fans and a beacon of excellent real ale when good beer was a relatively rare sight. Its function room, lost c2011 due to redevelopment as flats, served as a de facto headquarters and social space for many, among them the British Stammering Association and London’s independent brewers.

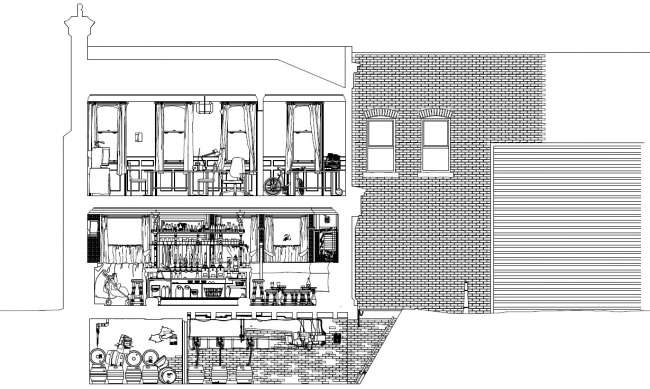

CROSS SECTION: showing the internal layout and delineation of space and uses within the pub (Credit: Liidia Grinko, Ming-Kun Huang, Sharah Khodabaksh and Mario Soustiel. Courtesy of Open City)

Our approach to the heritage of the pub is also highly constraining, in part because the UK continues not to be a signatory to the 2003 Unesco category of “intangible cultural heritage”. If the UK were a signatory, we could be advocating for the protection of the “practice” of the public house, on a par with cultural practices, crafts, foods and spaces worldwide. We could be arguing that one pub be protected as a piece of architecture regardless of its social offer and blind to its management, simply because its design is worthy of protection. We could also be advocating for policy to protect a great local not just from redevelopment or closure but also from a much broader range of actions that might limit its capacity to deliver what its community needs.

If we acknowledge that a pub is more than just its physical fabric, what are the intangible qualities it embodies that we should be worried about losing? Our journeys around the pubs of the British Isles tell us that a great many of our pubs are not “culture in aspic” – relics of another era – but active, lively cultural protagonists. They are spaces of exception from British cultural norms like the uneasy silence and the queue. They are places where society develops through chance encounters with people other than ourselves. They promote social interaction with strangers in a way that is extremely rare beyond their walls. As we become increasingly aware of the siloed thinking and echo chambers promoted by social media, the pub remains a place of sharing, conviviality and difference.

In Public House we explored the multiple ways that a pub, in the context of Greater London, might have significance. Illustrating this article are some of those examples, along with others drawn from further afield. These examples and many more highlight how, in celebrating the pub, we are celebrating not just a physical space but also practices, codes, behaviours, memories, customs and stories that are very easily swept away.

Of course the best form of conservation in this context is to practise what you preach and keep pubs alive through our everyday lives.

COMMUNITY ASSET - The Bevy, Moulsecoomb, Brighton & Hove

In challenging circumstances, some pubs take on a role in their community that wildly exceeds their basic remit. This is particularly true of pubs in community ownership, among them the Fox in Garboldisham, Norfolk, the Antwerp Arms in Tottenham and the Hope at Carshalton. The Bevy (or Bevendean Cooperative Pub if you insist) on a council-built housing estate in suburban Brighton, is perhaps the ultimate example of this, gathering funding during the covid-19 pandemic to deliver meals on wheels to vulnerable local residents. The loss of a pub in this context would be socially disastrous.

ARCHITECTURAL WONDER - The Cittie of Yorke, Holborn, London

IMAGE: The Cittie of Yorke with its historic barrels high above the bar and unusual private seating booths around the walls (Credit: Wikipedia)

Of course many pubs are architecturally significant, sometimes because of great age or eccentricity (Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem in Nottingham, half-buried in the foothills of the adjacent castle, comes to mind), but often because of the efforts of the breweries and their architects. Many of our cities are blessed with gin palace-style pubs or similar which are richly decorative, complex urban rooms, celebrated extensively in Mark Girouard’s important book Victorian Pubs (1975). The 1920s and 30s were another heyday of pub design, including Modernist and International Style examples but also richly evocative interiors that borrowed from a broader and weirder architectural tradition – among them the Gothic, Medieval hall fantasy of the Cittie of Yorke in Holborn.

CROSS SECTION: of The Cittie of Yorke showing the volume of the main bar space, with the booths to the left and the barrels to the right above the bar (Credit: Emilija Blinstrubyte, Aiva Dunauskaite, Maria Ghislanzoni, Neal Kazma and Christopher Kelly, courtesy of Open City)

CULTURAL VENUE - The Cumberland Arms, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

IMAGE: The Cumberland Arms pub at Ouseburn valley near Byker, Newcastle upon Tyne (Credit: Alamy / Horst Friedrichs)

Pubs promote culture, sometimes of diverse kinds but often in a way that generates a reputation and thereby becomes a bastion for a particular kind of culture or subculture. In the 1970s, the Black Raven in Bishopsgate, London, served as a hub for the Teddy Boy scene, while pub rock and punk were thrashed out largely in the basement of the Hope and Anchor on Islington’s Upper Street. The Cumberland Arms overlooking the Ouseburn in Newcastle, just the right distance away from the nearest housing, is a mecca for informal live music, hosting almost nightly musical get-togethers in a way that was once familiar but is increasingly rare.