PRESS RELEASE: Palatial historic home of HM Customs & Excise urgently needs a future

17th April 2020

One of London’s grandest Georgian public buildings is in urgent need of new uses. With its 140-metre-long columned frontage on the River Thames, the London Custom House could hold its own alongside the great palaces of the River Neva in St Petersburg.

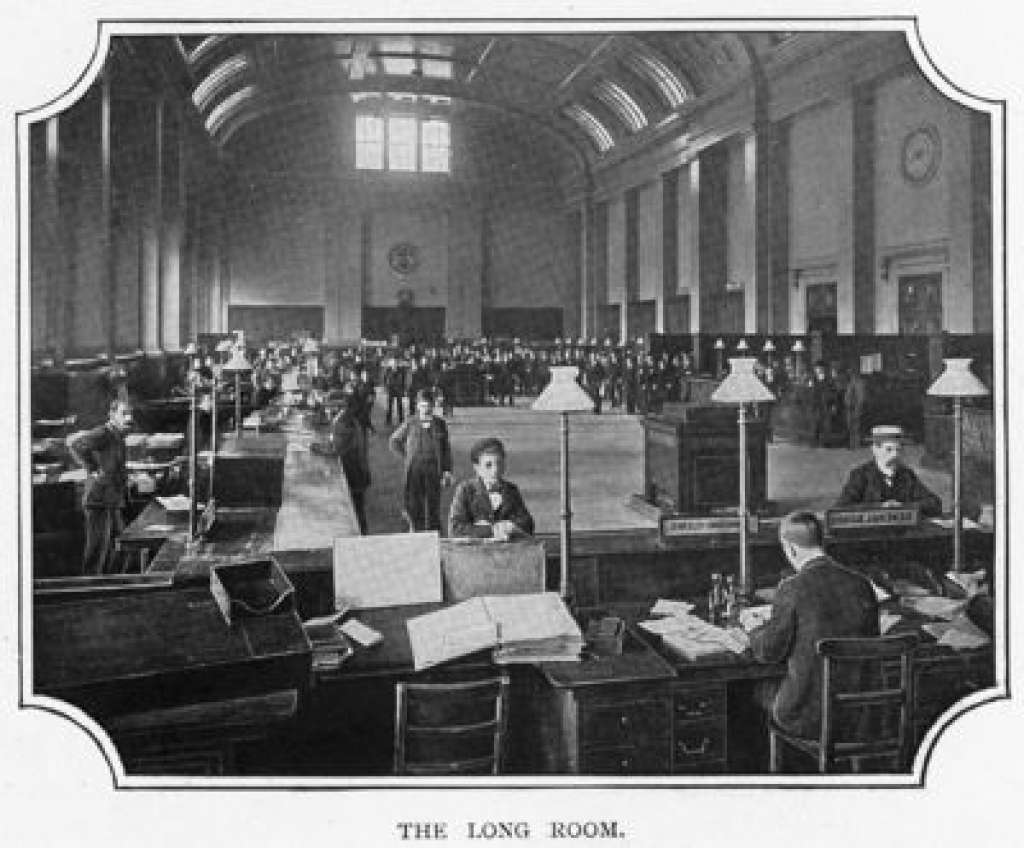

Completed in 1817, its magnificent Long Room, 60 metres in length, was one of the largest rooms in the capital, and thronged with people paying duty on all manner of exotic imports.

The site has been sold to property company Mapeley Limited which bought a substantial part of HMRC’s estate for £370 million in 2001. HM Customs will move out of Custom House in 2021.

Mapeley are now set to submit a major planning application, aimed at maximising the value of the grade I listed building. The site could then be sold to the highest bidder.

Marcus Binney, executive president of SAVE Britain’s Heritage, says: “this is a major opportunity for London which must be seized, not lost. We therefore call on the City of London Corporation to resist potentially damaging alterations to this major landmark, such as adding extra stories and penthouses on its roof. It is also important to retain the largely unaltered regency internal layout, which is a very rare survival in the City. Like nearby Somerset House and the British Museum, the Custom House is a magnificent expression of an Augustan Age when London vied with Paris to be the most elegant capital in Europe, defined by majestic public buildings."

Henrietta Billings, director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage, says: “The Custom House is one of England’s forgotten architectural treasures. It tells a remarkable story about the country’s history of trade and exchange. After over 200 years in public hands as the home of HMRC, it is set for a new lease of life. This is a once in a generation opportunity to open up the magnificent spaces in a sympathetic way for a range of different uses that must serve as an asset for London’s residents, workers and visitors alike."

SAVE believes there is a case for looking at solutions similar to those undertaken at two other great Thames side landmarks, Somerset House and Greenwich Naval Hospital. In both cases, trusts were set up to maintain the historic buildings, open parts to the public, and attract a mixture of tenants including museums, universities, hotels and restaurants. In SAVE’s view, public benefit and public access must be provided at Custom House, including the creation of a public promenade on the river terrace.

Today only river cruise passengers catch a passing glimpse of the building’s frontage, built of unblemished white Portland stone, glowing in the sun. The river terrace is closed off to the public and serves as little more than a desultory private car park.

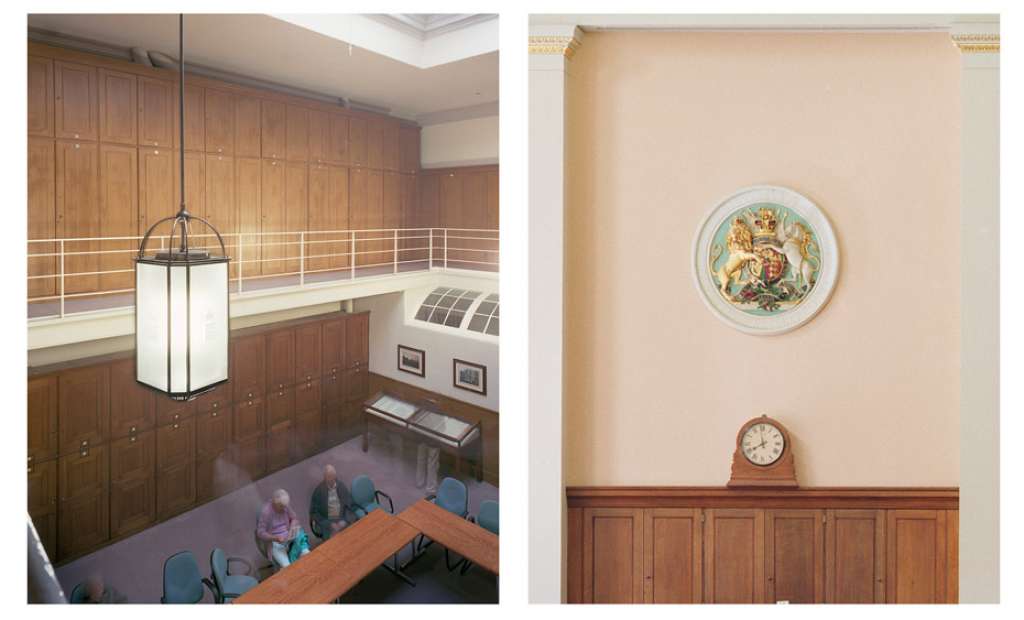

The Long Room is more than twice as long as the Great Hall at St Bartholomew's Hospital (27 metres) and most City livery halls. Adjacent to it is a Robing Room as large as a cathedral vestry, with numerous handsome cupboards, lockers and an upper level reached by an encased staircase. The grand entrance hall opening off Lower Thames Street leads to a grand staircase connected to arched galleries overlooking an impressive internal courtyard.

The ground floor includes the impressively columned King’s Hall (now Queen’s Warehouse), built to store confiscated goods. Memorabilia include important war memorials to Customs and Excise Officers who lost their lives. The basements have fireproofed arched vaults dating from the regency period.

The layout contains a great variety of offices and office suites, designed for different ranks of officials - many with tall sash windows and glorious views over the river. Numerous rooms retain their original panelling and handsome black marble fireplaces.

Given the importance of the Custom House, SAVE holds that any new use must go with the grain of the building and respect not only its character, but also its remarkable fabric and layout. Hotel use could be acceptable for part of the building, especially in the east wing which was rebuilt to a new plan after second world war bombing.

The terrace is less than 500 metres from the entrance of the Tower of London, a UNESCO World Heritage Site which last year attracted over two million visitors.

Marcus Binney adds: “the City of London has many small green spaces, churchyards and gardens which are very well planted and maintained by the Corporation. But it has few larger open green spaces, and the City should seize this opportunity to create a new public promenade on the river with seating and outdoor cafes.”

History of The Custom House

The Custom House has served for hundreds of years as the headquarters of HM Customs and Excise, a government organisation with its own romantic and often secret history of fast-moving cutters, intercepting pirates and smugglers stretching back to the 1690s. HM Customs claims to be the oldest law enforcement agency in the world, with the first recorded Customs Duty dating from 743AD.

A custom house has stood on this site since medieval times. The Elizabethan Custom House, dating from 1559, was built of redbrick with octagonal towers reminiscent of St James’s Palace. Destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, it was the first building King Charles II proposed for rebuilding, giving the great Sir Christopher Wren his first commission in London.

Wren’s superb building, which contained a magnificent long room, was gutted by a savage fire and was rebuilt by Thomas Ripley in 1718-25, but was destroyed again by fire in 1814. Fire was a constant danger due to the flammable goods (often confiscated) stored in the building, most notably gunpowder and spirits.

In 1817, rebuilding was entrusted to David Laing, a pupil of Sir John Soane (architect of the Bank of England), who produced a magnificent folio volume illustrating his grandiose plans. However, his failure to supervise the contractor resulted in one of the great corruption scandals of the age and destroyed Laing’s reputation.

In 1825, seven years after completion, the centre of the façade collapsed, bringing down a large part of the Long Room including Laing’s elegant saucer-domed ceiling.

The centrepiece was then rebuilt by Sir Robert Smirke, architect of the British Museum, with Ionic columns and a barrel-vaulted Long Room behind. Rows of customs clerks would deal with merchants, ships' captains and brokers in clearing goods and ensuring tariffs were safely collected.

ENDS

Note to editors

1. For more information contact Henrietta Billings, director of SAVE Britain's Heritage on 07388 181 181.

2. SAVE Britain’s Heritage has been campaigning for historic buildings since its formation in 1975 by a group of architectural historians, writers, journalists and planners. It is a strong, independent voice in conservation, free to respond rapidly to emergencies and to speak out loud for the historic built environment.